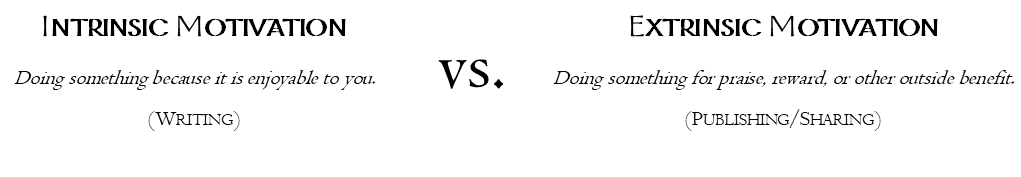

It has been a couple months since the last Authorly Advice blog, and that is due in part to this month’s topic: preparing series or worlds in the event that you may not be able to complete them in a timely manner (or ever).

I should preface this by saying that this year began with my getting a traumatic brain injury. Still now, nine months later, I am having major issues with life tasks and writerly tasks that used to come naturally to me. If I actively try to think about something—anything—my brain just fizzles into blank static. This happens when I try to remember something someone said to me, when I try to come up with story details, or when anyone asks me a question of any kind.

I’ll say something, and then two seconds later, my husband will ask, “What did you just say?”

*static*

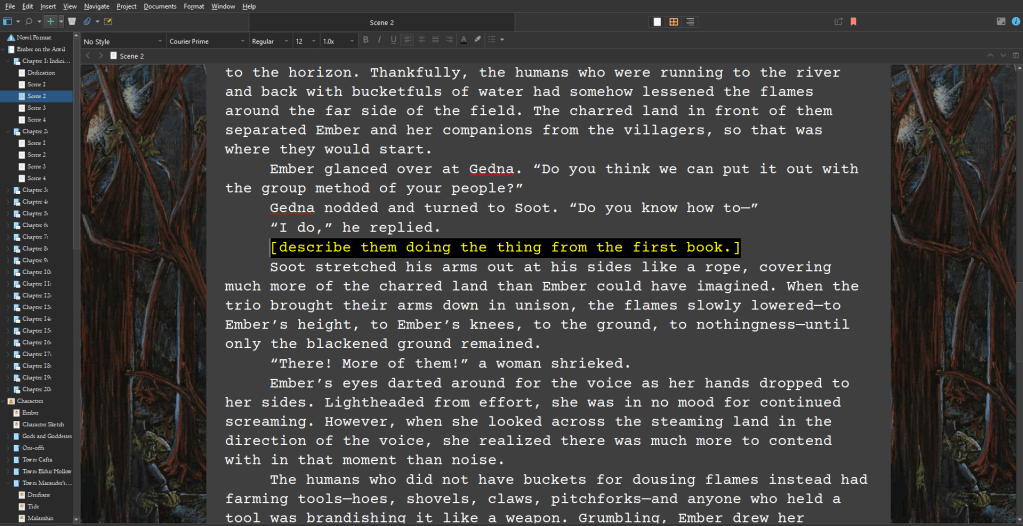

I’ve been working this entire year on memory care and other brain therapy to restore my previous function, but the neurologist told me flat-out that I may never regain my previous function—and if I do, it may not be for a year or more. I’ve now firmly slid into the longest period between novels since I published my first novel in October 2020. Yes, there have been four novels and two companion books in the past five years, but Ember in the Forge was published two years ago. It has been two years between novels. Part of that was due to my work on the D&D core book and part to some personal matters that took precedence, but there was six months between the first book and the second book. I know the story, but when I sit down and try to write, my brain fizzles into static after less than an hour. Every time. So I’ve started to make preparations just in case I lose my ability to continue to write my novels. I’m not there yet, but I want to make sure I’m prepared in case I do get there.

Readers and Incomplete Series

Many readers will see the first book in a series—or any incomplete series—and choose not to start the series until it’s finished just in case it’s never finished. Most series that are started are finished, but sometimes an author will pass away in the middle, will have some sort of incapacitating accident, will no longer be able to secure publishing, or will just decide to give up on the story.

Perhaps one of the most known modern incomplete series is Game of Thrones. I believe we may be nearing a decade or more since the last possible update on Winds of Winter (the next book in Martin’s planned series), and it has become a running joke that the story will never be finished. When the TV show passed the completed timeline, the showrunners were given more creative freedom with the later episodes. It is often argued that the reason the final season was so widely disliked was because the showrunners ran out of source material. A show that was beloved was then ended in a way that left many fans feeling like their time had been wasted.

Many readers—understandably—do not want to take the chance that a story will remain unfinished or will be picked up by someone who will canonize a story that may go against what was estabilshed. If a story remains incomplete, the cliffhangers left like that poor guy in Between the Lions in perpetuity, readers will be left unfulfilled as well. While those who really know us will (or should) care about the “why” behind an incomplete series, readers will be more disappointed in the story left without an ending. Some readers may never experience your world at all because they know that it is incomplete and will remain so. Some will try to fill the gaps on their own. While fanfiction should be encouraged, a story left incomplete opens the door to conflicting stories, arguments, and perhaps a fan theory becoming canonical simply because the author never finished and someone had to.

Preparing for the “Just in Case”

If you care about your world and the stories you have created for it, and you have series planned but not written, prepare for the “just in case” so that you have something together if the writing stops.

Whether you’re a planner, a pantser, or a plantser, there is some element of the series you can create a notes file for. In a series, even pantsers have to do a certain amount of planning to ensure there are no continuity errors between novels. That is where to start.

The amount of series trajectory notes you have depends on how many series you have planned. Let’s start with one series.

Preparing a Single Series

Actually preparing a single series can be difficult, especially for pantsers, but the idea is to write down anything that is important about the story just so it’s written somewhere. Even the pantsiest pantsers know how they want the story to end. Even if they allow the story to take them on a journey, and the meat of it changes based on how the characters transform in the writing, they know where they had intended it to go.

Completing notes for a series can be as simple as saying:

- “In this romance duology, the main character will fight with the love interest about something that seems to be relationship-ending, there will be some secondary love interest that comes in, but the MC will eventually end up happy with the book 1 love interest at the end.”

- “In this crime trilogy, the detective will have a setback related to a personal issue with the second victim. The murderer will be seemingly revealed at the end of the second book, but that’s actually a frame job. The third book will reveal that the murderer is actually the CSI who has seemed a little too helpful the whole time.”

Or, to add a bit more, as more of a plantser:

- “In this western duology, Texas Tony is the sheriff of Lone Creek who has been warned of the arrival of the gunslinger Bob, who has plagued all the nearby towns. He’s trained his deputies to face Bob and his posse, but the first book ends with a standoff, Tony getting injured, and Bob getting away. All seems lost. The first book starts with Tony recovering with he local doctor, determined to find Bob and beat him. As soon as he is able to ride, he gathers volunteers to search for Bob. Book two is all about Tony’s search for Bob. Tony follows Bob into a dangerous canyon, and when Tony and his men are separated and Tony is stuck in a crevasse, Bob is the one to rescue him. Tony then learns that Bob was actually an amateur Texas Ranger who got in over his head. Tony and Bob team up, and with Bob’s inside knowledge, Tony is able to find the posse, and together they bring in all the bad guys.”

Or, as a planner (spoilers for Lord of the Rings; pulled from Tolkien Gateway and BookCaps and revised):

- Overall Summary (The Fellowship of the Ring): Introduction to Middle Earth, beginning with hobbits. Frodo gets the ring from Bilbo. Gandalf returns nine years later and tells Frodo that the ring he has is evil and needs to be destroyed. He has Frodo leave the Shire. The hobbits set off to Bree. In Rivendell, they form the Fellowship (Frodo, Sam, Merry, Pippin, Gandalf, Boromir, Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli) and begin to walk to Mordor. They are chased by agents of Sauron and Saruman. They end up going through the mines of Moria, an old dwarven mountain, but while they’re there, they face goblins and a Balrog and lose Gandalf. They seek solace in Lothlórien, another elven village. Soon after leaving Lothlórien, they face a conflict when Boromir tries to take the ring from Frodo. Orcs attack while the Fellowship search for Frodo. The Fellowship splits during the search, and Frodo and Sam head off alone.

- Part 1

- Chapter 1 (A Long Expected Party): The hobbit Bilbo’s 111th birthday party arrives. We learn about hobbits and are introduced to Bilbo, Gandalf, and Bilbo’s nephew, Frodo. During the party, Bilbo makes a farewell speech and then turns himself invisible. He leaves his magic ring and all his possessions to Frodo, and Gandalf warns Frodo not to ever wear the ring or tell anyone about it.

- Chapter 2 (The Shadow of the Past): As the years pass, there’s unrest outside the Shire (where Frodo lives). Gandalf becomes worried and wants to test the ring to see if it’s the One Ring. He asks Frodo to give it to him, and Frodo doesn’t want to; the wizard tests it and learns that it is the One Ring. Gandalf tells Frodo some of the history of the ring. Frodo is scared and wants to give the ring to Gandalf. Gandalf refuses and says the ring must go to Mordor and be cast into the fires of Mount Doom. Gandalf sends Frodo and Frodo’s gardener, Sam, to Rivendell with the ring.

- Chapter 3 (Three is Company): Frodo sells his home and buys a house outside the Shire, using that as a pretense for his departure to Rivendell. Frodo, Sam, and Sam’s friend, Pippin, begin their journey. Along the way, they become afraid when they hear hooves and hide from a black rider. After this, the hobbits stay off the road. Along the way, they meet some elves and are protected by them through the night. The elves warn the hobbits to stay away from the black riders at all costs because they are servants of Sauron.

- Chapter 4 (A Short Cut to Mushrooms): The hobbits meet Farmer Maggot from taking a short cut, and he gives them some of his prized mushrooms. Merry joins them at the end.

- Chapter 5 (A Conspiracy Unmasked): Takes place at Frodo’s new house at Crickhollow. The title refers to Frodo about to tell Merry and Pippin about his quest, whom he had previously believed not to know about it, and they tell him that they had known much of it all along. They also meet Fatty Bolger. Frodo decides to leave the next day through the Old Forest, as it is an unexpected direction, rather than travelling on the roads.

- Chapter 6 (The Old Forest): Although trying to avoid it, the hobbits get lost and travel to the River Withywindle. Merry and Pippin are trapped inside Old Man Willow and are freed only when Tom Bombadil arrives.

- Chapter 7 (In the House of Tom Bombadil): Tom knows much about the hobbits, and even tries on the Ring, yet it does not have any effect on him—it does not make him invisible. Frodo tries on the Ring then to see if it ‘works’, and Tom Bombadil is also able to see Frodo while he has the Ring on.

- Chapter 8 (Fog on the Barrow-downs): Travelling through the Barrow-downs, the hobbits are imprisoned by Barrow-wights in a barrow, from which they are rescued again by Tom Bombadil. The hobbits are given daggers from the treasure in the barrow.

- Chapter 9 (At the Sign of the Prancing Pony): The hobbits reach the Prancing Pony inn at Bree, where Frodo uses a false name, Underhill. Later, after singing a song on a table, he trips and accidentally puts the Ring on his finger, disappearing, which causes a commotion.

- Chapter 10 (Strider): Strider, who had at first seemed menacing, turns out to be friendly. The innkeeper, Barliman Butterbur, gives Frodo a letter from Gandalf, which tells him that Strider is a friend of Gandalf’s and that his real name is Aragorn.

- Chapter 11 (A Knife in the Dark): The hobbits set out with Strider from Bree on foot after their ponies had bolted when Black Riders arrived at the inn at night, who had also attacked the beds which they were supposed to be staying in, though Strider had them stay in another room. They buy a pony to carry their luggage from Bill Ferny. They pass through the Midgewater Marshes, and reach Weathertop, just off the Road. There they are attacked again by Black Riders. Frodo puts on the Ring to escape them and is stabbed.

- Chapter 12 (Flight to the Ford): Aragorn takes the hobbits off the Road and into the Wild for most of the journey to avoid pursuit by the Black Riders. In the Wild, they come across the three trolls turned into stone in The Hobbit. Eventually, they return to the Road and meet an elf of Rivendell. He places Frodo on his horse and hurries them towards Rivendell. When they are almost to a ford, they are ambushed by the Black Riders. The elf’s horse carries Frodo across the ford. The Black Riders are washed away in a flood.

- Part 2

- Chapter 1 (Many Meetings): After awakening from a long sleep, Frodo meets Gandalf and Bilbo again, as well as Glóin from The Hobbit, Elrond, and others.

- Chapter 2 (The Council of Elrond): A council attended by many people; Gandalf tells the story of his escape from Saruman; they decide that the ring must be destroyed and Frodo offers to take it to Mordor. A fellowship forms, with representatives of humans (Aragorn and Boromir), elves (Legolas), and dwarves (Gimli, son of Glóin), the hobbits who are already there (Frodo, Sam, Pippin, and Merry), and Gandalf.

- Chapter 3 (The Ring goes South): The nine members of the fellowship travel south; they try to take the road over a snowy mountain but are forced to turn back.

- Chapter 4 (A Journey in the Dark): After confronting a pack of Wargs during the night, they travel to the gates of Moria, where they have to deal with a tentacled water monster in the lake in front of it. Gandalf eventually opens the doors using a magic word. They reach the tomb of Balin from The Hobbit.

- Chapter 5 (The Bridge of Khazad-dûm): Attacked by orcs and trolls, the Fellowship tries to make their way to a bridge, but Gandalf falls during a confrontation with a Balrog on the bridge.

- Chapter 6 (Lothlórien): The company meets the elves of Lothlórien. The elves reluctantly agree to let Gimli the dwarf pass. An elf guard takes Frodo to a hill.

- Chapter 7 (The Mirror of Galadriel): The company meets Celeborn and Galadriel, the leaders of Lothlorien. Frodo is shown the mirror of Galadriel, which reflects visions.

- Chapter 8 (Farewell to Lórien): The elves give them cloaks, elf bread and other gifts; they leave Lothlórien on boats.

- Chapter 9 (The Great River): They notice Gollum following them down the river on a log; they reach a waterfall, where they must choose between travelling on the east or west bank of the river to pass the falls.

- Chapter 10 (The Breaking of the Fellowship): Boromir tries to take the Ring from Frodo, who puts it on to escape him. Other members of the company split up trying to find Frodo. Frodo and Sam go across the river alone.

Do the same for the other two books in the series. Either just have bullets for important details or have bullets for planned chapters. Include the chapter names and character names or just descriptions. Planners often have the whole book outlined by chapter, with a couple sentences per chapter, anyway. While planning this all out doesn’t lock you into those details if the story does change as you write it, you do have an extremely detailed outline in case you don’t. While this long outline seems excessive, it is on par with many planners’ notes for their books as they write them. This just involves an extension of that for the full series.

Preparing Multiple Series:

If you’re writing multiple interconnected series, and all those series are part of an overarching story or pieces are needed to understand the whole, you may need to prepare multiple series. Sometimes, series just happen to connect or each are entirely separate ideas within the world. If your additional unwritten series do not affect the established story (or simply call back to it in a nice way for fans of the previous books), you may certainly prepare notes for only the series you’re currently working on and leave anything else out of your “just in case.”

- Suzanne Collins wrote the Hunger Games books. Since the series was completed and all the prior films made, she has written two standalones that function like prequels. They provide more information about established characters, but the histories of those characters was not needed to have a complete story. All three books in the trilogy were. She could have prepared notes about various character histories or futures as a “just in case” or “maybe one day I’ll write these,” but they are more optional.

- Tamora Pierce’s Tortall series could go either way. While reading about Rebekah Cooper is not necessary to know George’s (or Faithful’s), it adds another layer to the world. While Daine’s story is interesting and unique, it is not strictly necessary to know Kel’s. However, Alanna’s does feel necessary to understand elements of Tortall that are not otherwise explained—especially when it comes to how her story affects Kel’s and how her actions (and George’s) affect Aly.

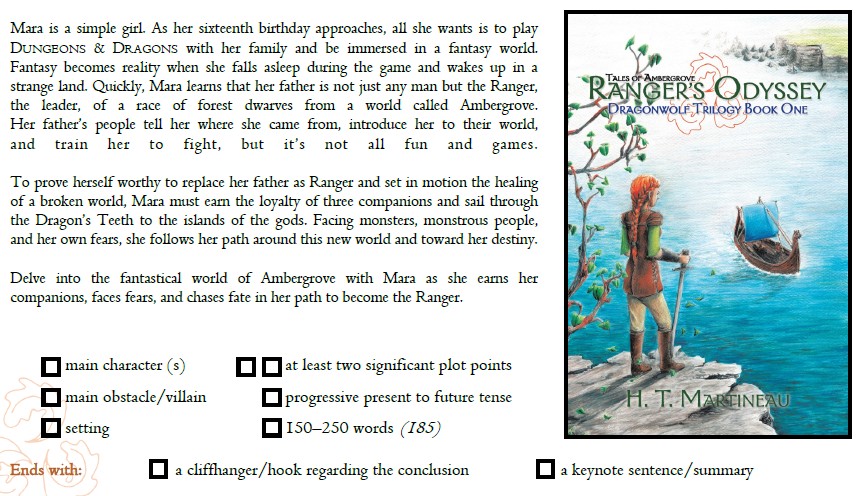

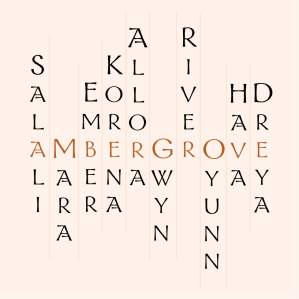

- My Tales of Ambergrove saga spans a single overarching story in nine series and five standalones. While each main character has their own story, and that story is more or less complete by the end of their series or standalone book, there is a single worldly goal that was hinted at in the first book. Every series and standalone in the planned books is intended to piece together that final ending. Mara began the Fourth Age in Ambergrove, but the Fifth Age will begin at the very end of the last planned book. While, at face value, the story is complete when Mara’s is complete, and the story will be complete when Ember’s is complete, and later Korena’s, and so on, the planned story will not be complete until the end of Dreya’s. Because I have planned for these all to connect and how each puzzle piece fits together, if I were to be unable to complete all the planned books, I need to have a “just in case.”

The past few months, and carrying on through the end of this year, I will be putting that together. So, what does that look like?

Well, for the initial planning of the series before I’d published all of the first trilogy, I planned out all the main characters and what part of the world their story would involve. I’ve known for years which main character would focus on bonds between elementalists and which would focus on the establishment of a new society, which would be about the dragons, which would be about the humans, and so on. I only had a couple sentences—a basic idea—but I knew how many stories there would be and who would drive them (pictured with details blurred).

To have a “just in case,” I need more than that. Start with one or two sentences for each series.

- “Mara is forest dwarves and bringing back the magic.”

- “Ember is mining dwarves and the establishment of the magic.”

Build from that. Include one sentence about each book. What’s the one most important detail from that book? If you aren’t sure how many books will be in the series, skip to just beginning and end. How will that story start in the first book and how will it end in the last book? If you know how you will split it by book, include that. How will this story connect to the other series in the world? What important information can you provide about this series that is relevant if you are unable to complete it?

Start with book outlines in however much detail you’d like to provide, but also include general notes about how the world changes and important elements for the whole. Compile all these notes into one single file, and then save that file as a PDF. Why PDF? Because PDFs are format locked. They are unaffected by changing screen margins, font availability, or other device differences. Why one file? So it’s coherent, cohesive, and doesn’t require any amount of scavenger hunt on your part or on the part of whomever is releasing your “just in case.”

Once you have included all you intend to include and have saved your single PDF, upload it somewhere other than your personal files. Email it to someone, save it to a cloud (and give someone else the download link), upload it to your website and leave it in a draft page so it is not released until the person operating your website chooses to release it. Have it ready.

When “Just in Case” Happens

Have a plan for how to share. Will you plan to share what is incomplete if you are unable to write more? Will you plan to share only in the event of your death? Will you plan to share only with a contracted few, such as another author who may be continuing writing in those stories with your blessing?

Whatever the case may be, have a plan so that you haven’t put everything together for nothing. Print out a copy and have it included in your will how that information should be handled. Have an agreement with someone else for how they will publish an unpublished webpage or share a post or video or other media.

If you are planning for your “just in case” happening while you are still able to release this information, decide at what point you’ve reached that time. Will it be after you’ve gone five years without publishing the next book? Will it be if an accident has left you unable to write? Will it be when you have reached an age that just keeps presenting you with more roadblocks than opportunities? Maybe when you have children or grandchildren or when you reach retirement age by other standards. Decide for yourself when that is.

If you just want to have them together for if someone asks and you do not plan to release all of it, that’s valid as well. Having these notes together allows you to have a compilation of everything you were able to come up with when you were able to come up with it—in case you are unable to fill those gaps organically later on.

That’s all it’s for: just in case you need to have the basic outline of the rest of the series in the event that you are unable to come up with it one day and need to provide it.

The pillars of Ambergrove are documented, and I will soon have the rest documented and an outline page for the website drafted and plans in place in case this brain injury prevails and I am unable to erect all ten pillars.

Conclusion

This advice blog has a rather narrow topic, but it’s a relevant one for anyone writing series. We want to think that we’ll be able to write and publish everything we’ve planned, but there are sometimes things that get in the way. Once your first story is out there and you have readers, it is your responsibility to those readers to ensure that they are not left without closure if you were unable to complete what you started sharing with them. Just in case.